The river which early people first encountered,

probably over ten thousand years ago at the end of the last ice age,

looked quite different from the river of today. From the mountains to

the sea it was a braided stream, broken up and meandering restlessly

back and forth along broad gravelly strips of land which were grazed

by giant herbivores. There was no Chesapeake Bay in those days before

the sea level rose with the melting of glacial ice, only the great Susquehanna

River bearing south to join the James in carrying fresh water over the

exposed continental shelf. There were also no fish leaving the ocean

en masse each spring to spawn in the fresh waters of the James. These

first people, called Paleo-Indians, saw no particular advantage to settling

along rivers since there were few fish to eat. Usually they stayed ill

small groups, moving restlessly through the forests of northern spruce

and pine, hunting mammoths and mastodons .

The climate continued to warm. As the

snow caps melted on the mountains, the James carried vast loads of eroded

silt in the rising waters which were cutting down into its present bed.

The wide floodplains became more fertile, the forests changed, and more

Indians came to hunt, fish, and gather food, especially around the mouth

of the river.

Several millennia ago, the Chesapeake

Bay began forming as the rising seas invaded and drowned the Susquehanna

and the lowest reaches of the James. As the Bay became saltier, anadromous

or freshwater spawning fish such as shad, herring, and the giant sturgeon

began ascending the James, perhaps four thousand years ago. Indians

whom anthropologists have labeled the Savannah River people also came

to the river's mouth and eventually moved upstream, following the fish,

sometimes settling on the same sites chosen by other tribes centuries

before. They understood well that "April is the cruellest month." The

blooming of spring life ironically coincided with their starving times,

for in spring the game was hidden by the new growth, the nuts were rotten,

and harvest of berries and wild grain was months away. For them the

river--with its dependable fish runs from March through June and the

wild grains sprouting on the floodplains--promised survival, no less.

It determined where, how, and even whether they could live.

In

that wilderness the river was the only road, and virtually every Indian

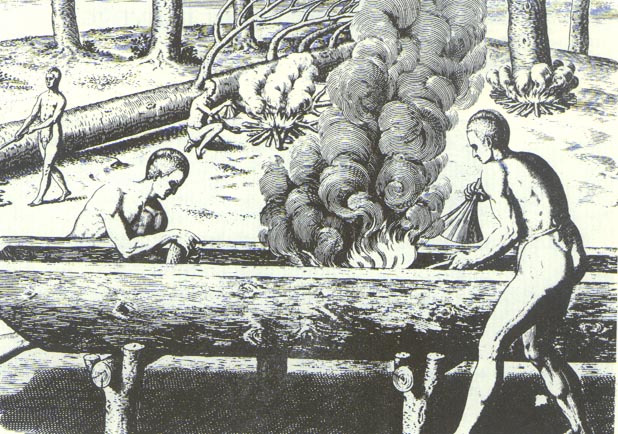

village was located on a river or a large creek. Rough canoes, burned

and scraped out of virgin timber, made the exchange of goods possible,

sometimes over remarkably long distances. The water level was lower

then, as was the level of the sea, but the James could still be an unpredictable

river, often reduced by drought or swollen by flood, and its swift currents

ran in only one direction. Perhaps the advantages of the linkage it

provided were offset by the necessity for the groups to spread out,

for even the fertile floodplains in the piedmont region could not support

large numbers of people after the fish returned to the sea.

In

that wilderness the river was the only road, and virtually every Indian

village was located on a river or a large creek. Rough canoes, burned

and scraped out of virgin timber, made the exchange of goods possible,

sometimes over remarkably long distances. The water level was lower

then, as was the level of the sea, but the James could still be an unpredictable

river, often reduced by drought or swollen by flood, and its swift currents

ran in only one direction. Perhaps the advantages of the linkage it

provided were offset by the necessity for the groups to spread out,

for even the fertile floodplains in the piedmont region could not support

large numbers of people after the fish returned to the sea.

In some ways the river was a kind of natural

Berlin Wall which raised social and cultural barriers. Not surprisingly,

tribes tended to ally more with groups on their side of the river. But

the greatest demarcation was at the Fall Line. the buffer zone that

the Powhatan Indians named Paquachowng.

Above the Falls in the Piedmont Plain

were the Monacans, people of Siouian linguistic origins who were settled

in small groups along the river's floodplain. They were family centered

and rarely roamed far for their food, a "sedentary" people (as anthropologists

say) who preferred to catch the fish and gather grain which grew from

seeds first swept downstream from the fertile hills. They stripped and

felled trees on the islands and banks to encourage the seeds which were

gifts of the floods. Probably they did not actually plant crops of maize,

beans, and squash until about 1000 A.D.

Archaeologists now believe that these

piedmont people lived in what has been termed a segmentary confederacy.

The small bands stayed to themselves except for the necessary marriages

and battles against common enemies, especially the aggressive Iroquois

who kept raiding from the west. By stretching along the river, they

were quite literally segmented in organization. There may have even

been substantial language barriers between the tribes on the James and

those on the piedmont portion of the Rappahannock River to the north.

There was little political organization of the basically egalitarian

Monacans, although there was a "central place" at Rassawek, on the broad

alluvial land between the James and the Rivanna rivers.

The Monacans tended their own gardens

beside the great fresh water stream, occasionally challenging the territorial

boundaries of tribes below the Falls, though probably more to trade

their soapstone pottery than to gain food. Ordinarily they stayed well

above the buffer zone of the Fall Line where the Powhatan Indians sometimes

hunted.

The Indians in the tidewater river, of

Algonquin origin, were more numerous and closer neighbors, but they

were less settled. With little fertile floodplain available, since that

land had been drowned by the rising river waters, these Indians supplemented

farming by hunting deer, bear, and squirrel, fishing, and gathering

nuts and berries whenever and wherever they could be found. The life

of the Coastal Plain was highly diverse, with an abundance of different

food sources varying by season. Thus these tribes, which the English

identified as the Powhatans, stayed relatively mobile, moving from river

to uplands to swamps with their wigwams, following their food and camping

near fresh springs.

The wide river below the Fall Line, which

branched into many streams and marshes, offered easy access and communication

for a people who had learned early how to turn trees into dugout canoes.

This access, plus the need to coordinate food-gathering activities,

evidently encouraged a more sophisticated tribal organization than the

Monacans knew. Eventually more than thirty tribes joined in what by

1607 was called the Powhatan Confederacy, a loose hierarchical political

organization managed by the chief or werowance, the wily Powhatan, assisted

by Opechancanough. Chiefdoms were usually hereditary, passing through

brothers, then sisters, then the sisters' sons. Though allied, each

tribe roamed a clearly delineated territory.

Less is known about how the other major

barrier on the river, the Blue Ridge mountain range, affected Indian

culture. Here the river, without extensive fertile plains or the spring

fish runs, may well have played only a slight role in the lives of the

Iroquois who hunted in the mountains and roved in small bands through

the valleys of the James and the Shenandoah.

Although the James is one river, its divided

nature, then, spawned at least two cultures, with surprisingly diverse

structures. By adapting to the different conditions and rhythms of the

river, each developed in turn rather different styles of living. The

river was the prime shaper of their daily lives.

What we know about the Paleo-Indians or

the Monacans and the Powhatans before the year 1607 either has been

deduced from the projectile points and shards of a few archaeological

digs or was reported by the early colonists, especially John Smith.

Neither source gives much basis for understanding the Indians' deepest

emotions about the river. These we must surmise.

The first human beings to come to this

river were probably slow to gain any sense of mastery over the river,

and far slower to understand that any control of these relentlessly

flowing waters was possible or desirable. So intimately de- pendent

on the river were they for its sweet waters, its fish, its attractions

for game, its protection, even for a sense of location and direction,

that they accepted it as a major fact of their natural existence. They

took its gifts as they could, very likely unable to imagine that there

could be more. The rhythms of their lives were governed by those of

nature, as were those of the animals they hunted.

At some point in the dim prehistoric past,

these peoples became aware of themselves as being somehow separate from

nature. It was then that they began seeing and questioning the river.

How were they to explain its power? Its constant changes and yet its

perpetual flow? What if it should stop or go away? How could mere people

placate the anger of its flooding waters and lure the fish into reach?

'We have no way of knowing how or when

these particular people answered these and other questions about their

river. We do, however, have some idea of answers from other primitive

peoples, for the clues still lie at the base of myths and religions.

The river, like the skies, the forests, or the mountains, has long been

the home of powerful and inexplicable gods and a symbol almost too deep

for words for understanding birth, death, and life's renewal.

The ancient gods of the rivers were rarely

named or described, for like the river they were shapeshifters and some-

times even androgynous, as the Greek myths tell us. Some also had the

power to transform intruders into fish-men or fountains. Each river

or spring had its own god or nymph which guarded it and embodied the

sacredness of flowing waters. Nymphs who were given names could be nurturing,

for they sometimes raised children to be heroes, or they could be destructive,

visiting madness on any man who spied them at midday.

These watery gods commanded respect, veneration,

and even sacrifice, though not love nor strong roles in the mythic tales.

They were essentially unformed and metamorphic, often nameless, more

in the realm of the potential than the fully realized, even in the farthest

stretches of men's imaginations. Rarely did they interfere in the affairs

of men directly, for their link with primordial creation put them generally

beyond time and history. Yet when men sought wisdom and foresight, it

was often to the springs and fresh waters that they came to consult

with the resident maiden oracle, as at Delphi in Greece. It is no coincidence

that the finding of fresh water has long been called divining.

The river has been worshipped primarily

as the bringer of life, as germinative, containing the potential for

all forms of life. And so it was, in ways we are just now beginning

to comprehend. The Indians on the James seem to have venerated the river's

fertility. They learned that the river brought seeds in its flooding

waters, for their ax-heads still clutter islands of the piedmont James

where the Monacans once cleared trees to make certain that the seeds

flourished. Since they grew their crops on the floodplain, they evidently

understood that the silt deposited by the river, past and present, bore

the most abundant and fruitful vegetation.

But there is no way the Indians or other

primitive peoples could have consciously known that all animals breathing

the oxygen of the air had their origin in the fresh waters, nor that

the ages and ages of rains and erosion on the hard earth long before

man appeared, as the waters ran to the sea, had turned rock into soil

fit for life. Yet for almost every primitive culture situated on a fertile

river, whether on the Ganges or between the Tigris and Euphrates, the

recurring myths of creation show life emerging from a primeval watery

chaos. So it may have been for the Indians on the James, explaining

why they often placed fish on their hills of corn seed.

Whether these Indians ever felt compelled

to make drastic sacrifices to guarantee the fertile powers of the water

is un- known. It is improbable, though, for this is a relatively dependable

river, which never dries up. Nevertheless, this river is unpredictable.

There were surely fluctuations in the fish runs, as well as floods which

came too late and so submerged, not planted, the rough fields.

The early colonists, for all their meticulous

description of the curious dress and social habits of the "savages,"

were a bit derelict in recording the rituals of the Indians. What they

did notice, they usually could not understand. But a time- honored rite

of purification and sacrifice to the river is suggested by the account

of' William White, who lived with the Powhatan Indians during the summer

of 1607.

As Richard Hakluyt recorded White's story:

the morning by break of day,

before they eate or drinke both men, women and children, that be above

tenne yeeres of age runnes into the water, there washes themselves a

good while till the Sunne riseth, then offer Sacrifice to it, strewing

Tobacco on Water or Land, honouring the Sunne as their God, likewise

they doe it at the setting of the Sunne.

What the English interpreted as simple sun

worship and unnecessary bathing appears to include reverential recognition

of the cleansing powers of the flowing river.

The ceremonial sacrifice of tobacco, prized

by the Indians as a source of pleasure as well as a religious symbol,

especially after a storm, also astonished the colonists. Robert Beverley

assumed almost a century later that such rituals were intended to pacify

or conquer the river. He noted that "when they cross any great Water,

or violent Fresh, or Torrent they throw Tobacco, Puccoon, Peak ... to

intreat the Spirit residing there, to grant them a safe passage." The

colonists' explanations may well show more about their perspective on

the river as a force to be tamed than about the Indian worship of the

river's powers. Evidently many of the Indians' religious rituals centered

on the river. But the kind of spiritual wealth the sacrificial tobacco

represented had little meaning to the representatives of the London

Company.

Water also played a key role in Indian

medical practices. The roots and bark ingested for various ailments

were ground and infused in water. If external application seemed more

appropriate, water was used to make a poultice. But the flow of the

river was imitated most in the Indians' frequent use of sweating huts,

actually saunas in the Finnish style, followed by a plunge into cold

water to carry off "all the Crudities contracted in their Bodies," as

Beverley put it. Not incidentally perhaps, the Indians were consistently

described as very healthy people before the white man's diseases began

wasting them, an observation borne out by the archaeological record

of their bones.

The river must have also given the Indians

a peaceful sense of continuity, for it was the unending witness of past

and future generations. Trees could rot and hills could be diminished

by erosion, but the river kept on flowing. Though, like life, the river

runs in only one direction, somehow it is mysteriously and constantly

renewed. Surely here the Indians found both hope for immortality and

verification of the single direction of time, the bearer of loss and

death.

A myth now popular has it that American

Indians worshipped nature and its indwelling spirits from arm's length,

and that fear or reverence made them reluctant to tap nature's bounty.

Perhaps this notion has been fostered by those who have struggled to

preserve the more pristine wilderness areas where men left few if any

marks. But even those Englishmen who thought they had discovered virgin

land, a kind of untilled, primeval garden of Eden which lay awaiting

their god-sent cultivation and redemption, had to admit that the Indians

knew well how to use nature's gifts to fill their needs.

The accounts sent back to England are

filled with details about how the Indians farmed, fished, and hunted.

But, oddly enough, admiration for the effectiveness and ingenuity of

these practices did not become emulation. As John Smith wrote in the

fall of 1608, "Though there be fish in the Sea, foules in the ayre,

and Beasts in the woodes, their bounds are so large, they so wilde,

and we so weake and ignorant, we cannot much trouble them." The Indians

had no such problems. In turn, the English, like other European newcomers,

had no compunctions about trading copper trinkets for bushels of corn

and taking full advantage of Indian generosity at harvest time. But

as representatives of a superior Christian civilization, they felt that

they must resist the temptation to learn from savages.

The English had particular trouble understanding

the Indian concept of property ownership. Although tribes had territorial

boundaries, the idea of exclusive possession of the land was alien to

them. The land and the river belonged only to the people who used them,

when they used them, and to the generations yet unborn. They did not

even leave their river a single name. It was given many names in the

typical Indian fashion, names associated with parts of the river that

invited description (like the Falls) or, more often, with tribes whose

activities bounded a particular segment for a while. For the Indians,

a river and its people were connected by naming.

The Indians felt free to take from nature

what they needed to survive, but they took little more, and shared any

excesses from good harvests with less fortunate neighbors, even hungry

white men. Perhaps they felt that to use the gifts of the earth too

liberally, beyond what could be re- placed naturally, could waste what

they and their children's children would later need. Thus, though the

river had known Indians fishing its waters and settling on its banks

and islands for thousands of years, the water remained sweet and fertile.

They were effective fishermen, but they recognized certain limits. They

left few signs of their long tenure: two distinct kinds of arrowheads,

some Monacan pots of soapstone, a few stone fish weirs at shallow rocky

places, and possibly some sediment in the bed eroded from the lands

cleared above the Falls for farming. Nothing, though, really disturbed

the river or its life.

It would be a mistake to romanticize the

Indians' treatment of nature, forgetting that they were relatively few

in number and widely scattered (probably there were never more than

a few thousand in Virginia at most). They lacked tools to change their

environment seriously, even if they had wanted to. The Monacans in particular

used fire freely to clear trees from the floodplain, and the only reason

more soil did not wash into the river was that they saw no reason to

remove stumps or work over their fields. The effects of subsistence

living by a relatively small number of people could be easily absorbed

and repaired, if necessary, by natural processes.

But even granting these facts, we must

acknowledge that the Indians could literally see and adapt to the river's

processes far better than the white conquerers were willing to do, even

though they actually knew less "science." Their reluctance to take more

from nature than they needed, possibly from fear that nature might not

continue to provide so generously, and their respect for the river's

moods were attitudes alien to the people who were to displace them.

We cannot know for certain how the river would have fared under continued

Indian stewardship, especially if the population had grown, but it is

fair to assume that the river's subsequent history could have been different.

There is at least one place on the river

where it is possible today to look back through time, to glimpse the

continuity the Indians must have felt. About two miles up Powell Creek,

south of Hopewell in the tidewater estuary, is land high between two

marshes which several groups of Indians, especially the Algonquin tribe

called the Weyanoke or Weanoc, found to be choice living ground for

as long as nine or ten thousand years. In 1607 John Smith counted 340

people here and in four other Weyanoke villages on both sides of the

river. This location furnished fertile soil replenished from higher

ground, abundant fresh water from springs and the creek, wildlife which

came to drink and live on the quiet marshy creek, and protection from

invasion by men or floods. Neither eroded nor mined for gravel, the

soil over the bones and treasures of this culture remained untouched

for centuries. For the past six years, an independent group of archaeologists

has been digging at this spot, piecing together the kind of life and

death acted out on these banks .

There are not many places I would consider

hallowed ground, but this remote site would head my list. I had taken

barely ten steps before I found a shard of pottery over two thousand

years old with a surprisingly sophisticated fabric design pressed into

the river clay. A little digging revealed many more such shards along

with stone chips discarded from centuries of projectile point making.

These fragments lying in the fill from earlier digging may not have

been special enough for the archaeologists to keep after recording their

precise position, shape, and condition, but they made the ground literally

come alive for me. Under glass was the systematic proof of these early

people's growing mastery in shaping the stones and shells from beside

the river. Each object had its niche in the long history that the chief

archaeologist sketched for me as he chipped at a stone, making it an

arrowhead the Indians would have acknowledged as well crafted.

As we dug that afternoon, learning how

to name what we unearthed, we uncovered a midden, a kitchen pit topped

by deer bones with human teeth marks still on them. Speculating on what

might lie beneath those bones interested me more than actually finding

objects to measure or photograph, but then I am not a scientist. As

we sifted through the rich black dirt, I realized that even in a few

hours my eyes were beginning to refocus, to see new dimensions around

me. Roots and oyster shells were easy to discard, but almost nothing

else was tossed aside as we carefully felt for evidence of the ancient

folk who now seemed so close.

Even the creek seemed different after

we finished digging, now teeming with waterfowl and fish I had not noticed

before. We would find there none of the evidence of the Indians' lives,

though it was the water which had repeatedly drawn different groups

of Indians to this spot. I knew that I too would have to come back,

perhaps to help stand guard some warm night and to dream myself into

the spirits of these people my ancestors had once forced away from the

river.

Dig as we may, there is still much we

can only guess about the meaning this river may have held for the simple

folk on its shores. Was the river considered a nourishing mother, a

vengeful father, or both, like the androgynous god of the Nile? Were

its waters reputed to heal or to restore youth? Were its fish sacred?

Did the Indian myths of death speak of a journey across the river? Was

the pollution of the stream from which they drank forbidden, as it was

in India and Babylon? We can only guess. But we can be certain that

the river was vital to their emotional and spiritual as well as their

physical lives. What the Weyanoke dig teaches is that the Indians recognized

and responded to the river's living mastery for centuries, long before

the white man came with his civilizing guns, concepts of profit and

ownership, and faith that nature could provide liberally and infinitely.